Back in Flickr land the question was asked would buying an external light meter help one understand one's camera settings? As happens on the Internot, opinions surfaced from both sides. As such, it seemed prudent to make some information available on just how this light meter thing works, what it can and can't do for you and what you can learn from it.

What does the meter meter?

In a word, a light meter measures luminosity. That is, it measures the intensity of the light source you point it at in a unit called candles per square foot. In their simplest form, old-school light meters would give you a reading of how many candles/ft2 were present in the direction you pointed it. Advances in interface let the meter give you a reading either as an arbitrary scale (where "2" was more light than "1", but "1" and "2" didn't correlate to any specific units of measure) or as a series of f-stop/shutter speed combinations for a chosen ISO rating.

Hold on, let's backtrack...

In order to understand the so what portion of this, there's a little behind-the-curtains information that will be necessary. So, here's the big secret of photography, please keep it hush-hush: All photography is black-and-white photography. Yep, it's true. All photography, film, digital, black-and-white, color, slide, print, hell, even x-ray photography is always and forever black-and-white photography. Reason being, a piece of film or a digital sensor can read one and only one thing: luminance. (Starting to make sense, eh?)

In black and white film photography light strikes an emulsion full of junka that is sensitive to light. The more light, the more the junk gets affected, the darker the negative is at that spot and therefore (since it's a negative) the lighter the resulting print will be. Color film works exactly the same way, it just does it 3 different times. The light still strikes some light sensitive junk, but for color images there are three layers of the junk with various sensitizers in the mix to make the junk only react to a certain color of light. Until the final stage of development, those three layers are just 3 black-and-white copies of the image. During development the junk gets replaced with a colored dye in the same quantity as the junk before it. As those 3 colors stack in the 3 translucent layers all the other colors are created by subtraction. Digital sensors work the same way, but instead of layers of dye the sensor has three tiny receptors for each pixel. Each receptor is sensitive to only one of the primary colors and they're squished up close to each other so that they can pretend as though they were one atop the other like film layersb.

So, all any camera ever does is record the luminance each pixel of an image as some shade of gray on a continuous scale between pure black and pure white.

Ok, so what?

So now that we know that light meters read luminance and camera film and sensors record luminances, a mini A-HA moment occurs: "A-HA! I can measure the luminance with a meter, and then set the camera to record THAT luminance! EUREKA!"

Wait a second, there's a problem. Nowhere on your camera will you find a dial, button, knob or twisty-thing that says "luminance to record". So what use is this nifty measurement you can now make?

The magic of middle gray

Well, as it turns out, a decision has been made to help you out here. From the dusty days of yore, photographers have agreed that a "proper" exposure is such that the average of all the luminances in a scene would fall halfway between "darkest dark" and "whitest white". By virtue of some freaky science-y shit, that halfway point is equal to a surface that reflects 18% of the light that hits it. That shade is referred to as middle gray or 18% gray. You'll see little devices called gray cards that are printed to be exactly that middling shade to use as an exposure targetc.

The important part

So, when your light meter (either inside the camera or outside) says "shoot this picture at f/8 and 1/125", it is actually telling you, "If you use f/8 and 1/125 for this exposure, all the luminances in this scene will average out to the magical 18% gray". Plain and simple, that's all you'll ever get out of a light meter. There are light meters that will read a very small spot (oddly enough, they're called spot meters) and ones that read a wide area to average (which is likely what your camera does, and most of the hand-held meters you'd buy). Some cameras can be set to one of several metering modes (of which "spot" and "average" are typically included). But at the end of it all, the meter is still only telling you "the thing you're pointing me at can be rendered as middle gray using these settings..."

Your camera is a lying ass

Here's the bad news: as long as the scene you wish to photograph contains a pretty even mix of luminances from really dark to really light and everything in between, your light meter can give you an exposure setting that will do pretty well. However, if your scene contains an unusual amount of dark values, or light values, or really just a lack of mid-range ones, your meter will lie to you like your worst ex.

It's not really the meter's fault, of course. The meter just wants everything to be middle gray, but it has no idea what you're really pointing it at, or how you want the scene rendered. Let's imagine you're taking a picture of a jet-black car parked against a blazing white-painted wall. Well, your meter will dutifully do it's job of averaging everything out to middle gray, which will give you a picture with a dull, dark-gray car, and a flat, lighter-gray wall. This is, by the way, why everybody always gets gray-looking snow with auto-exposure cameras in the winter. The meter got confused with all that white and did its normal, middle-gray thing to it.

So how do you get any use out of a light meter?

All you have to do is take 1 more second before you snap that shutter and think about your scene. Now that you know what the meter is doing, you can predict when it's going to lie to you by examining your scene. If your intended target has a serious lack of middle values you can bet that your meter will screw up the exposure and give you dull, flat values. Your decision is which is more important, nice white whites, or nice deep blacks. If you prefer the highlights, give the shot a little more exposure than the meter suggests (thereby taking the grayish highlights the meter wanted and pushing them up to white), or, if you prefer the shadows, give a little less exposure (thereby taking the muddy shadows the meter wanted and pushing them down closer to full black).

If the scene in question is truly hideous with light and dark values, it may pay you to bracket the shot with a 1-stop increment over 3 shots (one shot as metered, one shot a stop under, and one shot a stop over that value).

A note on equivalent exposures...

Keep in mind as you delve into adjusting the exposure suggested by your meter the concept of equivalent exposures. Equivalent exposures is just the fact that an exposure at f/8 and 1/125 is exactly the same as f/11 and 1/60 which is also exactly the same as f/5.6 and 1/250. In fact, once you settle on an exposure, you can make exactly the same exposure with any other shutter speed by altering your aperture appropriately and vice-versa. Of course, your depth of field will change as will your camera's ability to stop motion, but the exposure itself will be identical.

So, can I really learn anything from my meter?

Yeah, you sure can. By carefully examining the scene you're photographing and then considering the exposure suggested by your meter (in-camera or out-) along with what the final output of that photograph looks like you can begin to understand what it means to expose a photograph properly. Taking notes as you shoot helps tremendously in this respect, and for you digital shooters you're lucky in that your camera already takes notes for you in the form of EXIF data.

For example, if you shoot a scene using either your camera's built-in meter or a hand-held averaging meter and get the image off the card (or the neg back from the lab) and look at it and go, "Meh, that looks pretty flat and lifeless. Everything is muddy"; perhaps you can think a moment and decide, "Yes, my meter lied to me, I should have increased the exposure a stop, that would've made the reflection coming off Mark Turnley's head appear as brilliant and shiny as it was to my eye!" The more you correlate what you see to what your meter sees, and relate those two to how the image turns out, the more you can learn the nuances of getting a truly great exposure.

So should I buy a hand-held, external meter?

The answer is both yes and no. Chances are no meter you will buy will be any more accurate than the one in your camera. On the other hand, what if the one in your camera goes belly up? Or, what if the one in your camera doesn't offer a spot metering mode, and you really want to use that? Or, what if you want to calculate a flash exposure accurately without firing frames and trusting your LCD display? All these are good reasons to buy an external meter. If you do buy one, try to buy the best one you can afford, and make sure it performs all the features you think you'll need. If you want to measure flash output, make sure it has a flash mode. If you want to do spot metering, make sure it has a spot mode/attachment. If you want to do incident readings (kind of the opposite of reflected readings: you point the meter FROM the subject TOWARDS the light rather than the other way 'round) make sure it has an incident attachment.

If, however, you're perfectly happy taking readings from your internal meter and don't mind switching between metered and manual modes (or whatever else you may have to do to take a reading but use manual settings) then the expense of an external meter is probably superfluous. You can count on the thing probably costing you at least $100, unless you delve into the used market (I got my flash meter for $40 on eBay).

No matter what you decide on the external meter issue, DO make sure that you start paying attention to whatever meter you use, and learn to know when it's lying to you.

Errata

Books you can read:

Nobody does it better than Ansel, and he wrote a whole book on getting a good exposure:

The Negative - It focuses on film and film cameras, but all of the exposure concepts apply just as well to digital photography.

John Hedgecoe's New Introductory Photography Course - Hedgecoe is a pretty knowledgeable guy, and he writes things in small, digestible chunks that are easy to read.

The list is practically endless, your local library will have tons of good books that cover exposure calculation in much greater detail than I've gone into here. As always, I hope this was helpful, and feel free to shoot me any questions that come to mind.

aThe "junk" is a silver halide, FYI.

bThis is why film can actually have a sharper image than a digital sensor, because the distance between the receptors creates chromatic aberration. Software in the camera corrects for it as much as possible without harming the image.

cYou can use a gray card to set your color balance, too. Include a shot of an 18% gray card with each set of photos and use that spot as the "pick spot" for your white balance adjustment software and you'll be dead on.

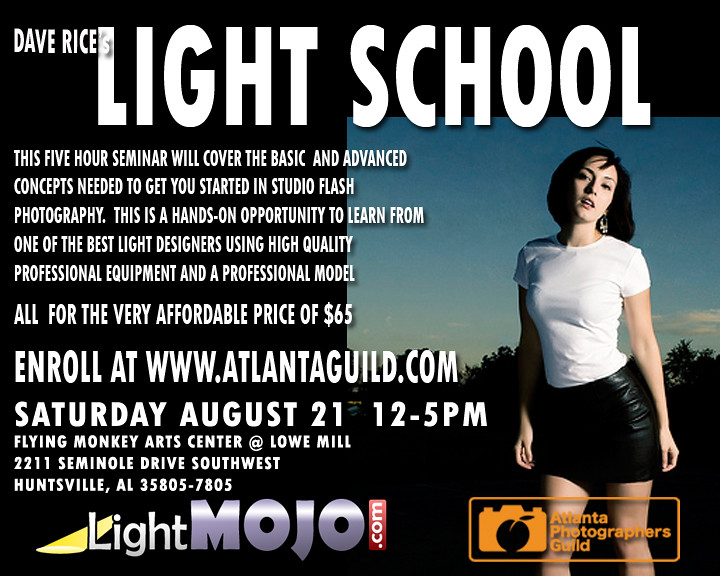

The Atlanta Photographers Guild is the most active group of professional and hobbyist photographers in the Atlanta area. Meetings are held on a bi-weekly basis and feature aspiring and professional models as subjects.

The Atlanta Photographers Guild is a co-operative. We meet to share technique, equipment, and a good time. Official meetings and workshops are way below the price point of the general market because we believe that photography is exciting and that excitement should be shared.

For more information, join our facebook group to keep informed of events and of course join us on flickr to get a feel for what the meetings are like, ask questions, or just have fun.

The Atlanta Photographers Guild is a co-operative. We meet to share technique, equipment, and a good time. Official meetings and workshops are way below the price point of the general market because we believe that photography is exciting and that excitement should be shared.

For more information, join our facebook group to keep informed of events and of course join us on flickr to get a feel for what the meetings are like, ask questions, or just have fun.

GOOGLE CHECKOUT FOR STUDIO RENTAL

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment